“Britain is not Great. Britain is Weird”

The Usher Hall voting >90% in favour of Scotland adopting its own independent currency.

On the 4th of November I spoke at the Scottish Independence Convention’s Building Bridges to Independence conference. As with my SIC talk in January, it fell to me to be the one with the graphs and statistics – this time on the topic of public finances and the impact of independence on Scotland’s budget.

The livestream of my talk can be viewed thanks to Independence Live and is the first talk in this segment.

Below the fold are copies of my slides with comments drawn from my talk and references to the points made. The slides can also be downloaded here.

Public finances and the question of whether or not Scotland can be independent is one that has dominated the debate during and since the 2014 referendum campaign but rarely during our annual self-flagellation at the hands of the GERS figures does the media go much deeper than simply stating the deficit and Scotland’s over- or under-spend compared to the UK average.

For folk who do want to go a bit deeper than that and who want to actually investigate the fiscal implications of independence need to go Beyond GERS.

For some sense of background, GERS – Government Expenditure & Revenue Scotland – was originally set up by the conservative government in 1992 for the explicit purpose of undermining the Scottish devolution debate. Its methodological limitations have been extensively discussed over the years – notably by economists Jim and Margret Cuthbert – Their library on the subject is a goldmine for enthusiasts of the topic.

Thanks to the efforts of the Cuthberts and others over the years, GERS has been steadily improved, especially in the years since the SNP came to power in 2007. The methodology currently used is a far cry from the 1992 version and whilst it can, and should, still be picked at and improved I am quite happy to accept the premise that GERS represents a fair summary of Scotland’s fiscal position as a region of the UK.

There is, however, something that no serious economist will dispute though.

Credit Rating agency Deloitte made the above statement in their 2016-17 State of the State analysis and whilst it is said with respect to Scotland’s fiscal choices post-independence it is also true that the simple fact of independence itself will have financial implications and these are worth exploring.

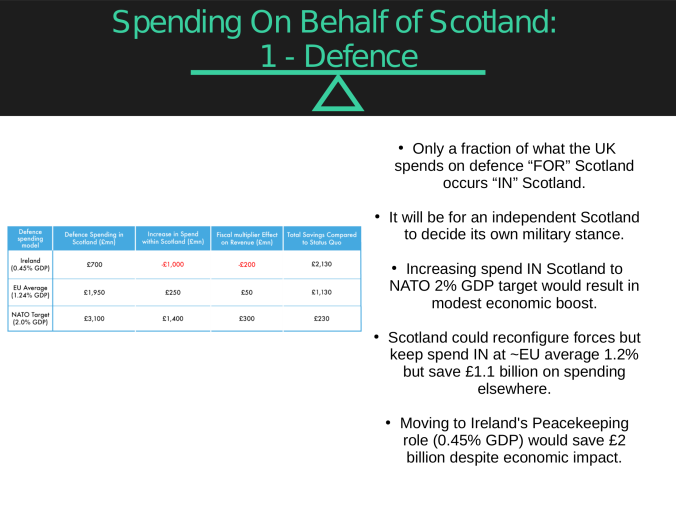

Scotland currently pays around £3 billion per year towards the UK’s defence structures but as best as can be told, only around £1.8 billion is actually spent IN Scotland. The remainder is spent either elsewhere in the UK or overseas.

Independence offers the opportunity to re-consider Scotland’s actual defence priorities and needs. Scotland would likely not need to prepare to be invaded by some other state nor to involve itself in invasions of other states. A rational look at Scotland’s actual defence threats finds them principally to be due to cyber-attack and climate change. Dealing with these threats will lead to very different spending priorities than currently seen as part of the UK. In terms of spending levels Scotland could, for example, follow the UK’s NATO target of 2% of GDP spending but the act of spending more of that IN Scotland will carry with it an economic boost. Modest though it might be (as military spending is one of the least efficient means of generating economy return) this could still result in around £200 million per year in additional tax revenue for Scotland.

Or Scotland could spend more-or-less as it does now within its borders. Doing this wouldn’t change our economy much but would mean direct savings of over £1 billion per year.

Or Scotland could follow the example of Ireland with its small defence force and involvement with UN Peacekeeping operations and could save over £2 billion per year (though presumably a portion of this would be re-invested in order to provide employment to former forces personnel).

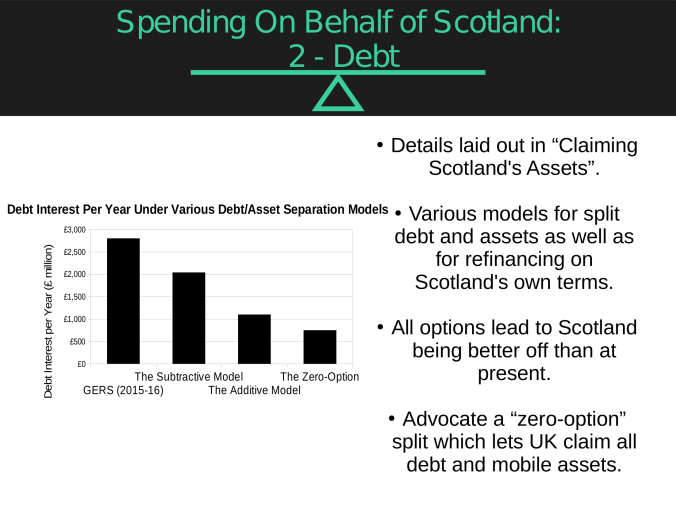

Drawing on my paper Claiming Scotland’s Assets, this slide outlines different scenarios under which the UK’s debt and assets could be split between Scotland and rUK. The Yes campaign in 2014 made the claim that a reasonable and proportionate split of assets and debts would take place – probably on population grounds – but the UK government’s stated position was that Scotland was “extinguished” by the 1707 Treaty of Union and therefore rUK would remain the “continuing” state to the UK whilst an independent Scotland would become a new one. The implication of this, in hindsight, is that the split would look less like the dissolution of Czechoslovakia – where the Czech Republic and Republic of Slovakia divided debt and assets by population – and more like the reconfiguration of the USSR in which Russia claimed ALL of the prior state’s debt.

The reason Russia did this was to bolster its claim to continuing to hold the USSR’s permanent seat on the UN Security Council – something which I’d wager the UK still considers quite valuable.

True, this arrangement would see Scotland cede right to any of the UK state’s mobile assets (fixed assets like buildings and mineral resources change ownership on geographical grounds) but when one asks what Scotland might actually want from the UK the list comes up rather slim. Perhaps roughly £10 billion worth of foreign reserves – though we also have other tools at our disposal to create the reserves we need, £1 billion or so worth of military equipment (though that could be dictated by the choices made above…Scotland doesn’t need an aircraft carrier, for instance) and we may need to spend around £10 billion to create various institutions like a new Central Bank.

All in, it’s a sum far below the £150 or so billion of our “share” of the UK’s debt so if the rUK wants to claim all of the UK’s assets so that it can continue to pretend to be a superpower then fine. Scotland will endorse their claim to the UN seat and let them have it.

(Not mentioned in my talk due to time constraints, it might also be worth pointing out that the UK is about to start making a series of major trade deals – starting with the EU. If the UK ceased to exist shortly after making them then these deals may well have to be re-opened so this might well be an even more important reason for rUK to claim UK continuing state status. Again – I’m happy offer the solution which would make everyone’s life easier and let them do that. That debt share may well be a relatively small price to pay to secure those trade deals.)

One of the more subtle points about the changes coming due to independence. Think of all the civil servants working in London on reserved powers “For” or “On Behalf” of Scotland. Whilst Scotland may make different choices about these reserved powers once they come to Scotland, it appears obvious that many of these government jobs will have to be replicated by Scotland. In Scotland.

One of the limitations of GERS is that the spending to support these jobs appears on Scotland’s expenditure line but the tax accruals from the people employed buying goods and services (thus incurring VAT or creating business demand which results in more tax from corporation tax, business rates and the income taxes from staff employed etc) ends up appearing on England’s income line. This probably makes sense for a regional accounting system but it means that the act of moving these government functions to an independent Scotland could mean a boost to Scotland’s GDP of around £2.5 billion which could mean an additional £1.3 billion per year in tax revenue.

It was stated in the 2014 referendum campaign that Scotland benefited from the UK’s “broad diplomatic reach” and, to an extent, this is true. The UK has one of the most extensive diplomatic networks in the world but it is largely built on a relic of Empire. Scotland probably won’t need the gold plated embassies such as the Foreign and Commonwealth Office pictured above. Running a more streamlined system, as Ireland does, could mean that Scotland could place an embassy in every country in the world for around £200 million per year. This is easily affordable and this sum is before Scotland considers proposals like embassy sharing or placing embassies strategically so that multiple countries can be accessed from one building near their respective borders.

One lesser know advantage of EU membership is that EU citizens have the right to consular support if they find themselves in a country in which their home nation is not represented. If a UK/EU citizen finds themselves in somewhere like Côte d’Ivoire Bhutan then they have the right to walk into the embassy of any other EU nation and expect to receive the same treatment as that embassy would give to one of their own nationals.

If Scotland chooses to remain in or rejoin the EU then this right opens the possibility of discussing strategic placement of embassies with our European friends and allies.

The repair bill for the Houses of Parliament could be over £5.6 billion meaning that Scotland’s share of that cost could be more than we paid to build our own Scottish Parliament. Similarly, Scotland’s share of the renewal of Trident could be over £17 billion worth of a total cost of £205 billion.

It should be said though that as significant though those costs are, they will likely be spent over a period of years or decades so in terms of taking a chunk out of Scotland’s deficit the effect will likely be fairly slight.

There are better reasons to stop paying for now illegal weapons of mass civilian slaughter.

The UK’s tax system is notoriously leaky. HMRC estimates that £35 billion is lost to the UK Treasury every year through evasion, avoidance, loopholes and error. Richard Murphy estimates it to be closer to £120 billion per year. Scotland has a real opportunity in independence to re-write this tax code from scratch and to bring it up to the standards of a modern, 21st century nation. The results could be profound. If Murphy’s estimate is correct and Scotland could recover just a third of its “share” of the tax gap then it could be worth around £3.5 billion per year. Murphy has written a paper for Common Weal outlining the principles that such a tax system would need to follow to achieve that goal.

Just from those examples outlined above, independence would be worth around £7 billion per year to Scotland – more than halving the current deficit. Clearly this would place an independent Scotland on far more secure fiscal grounds than it is on as a region within the UK. And, again, this is before much is done in the way of actual post-independence policy.

But perhaps we need to discuss just why Scotland has such a large deficit in the first place. It turns out that Scotland is not in a unique position within the UK.

The UK has recently started producing GERS-like accounts for the nations and regions of the UK and it turns out despite containing just 16% of the UK’s population Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland are somehow “responsible” for 55% of the UK’s deficit.

Of course nations are rarely equal so some regional disparity can be expected. So a comparison with other nations could be appropriate.

Luckily, Eurostat has already done this for us.

Above is the regional GDP/capita for several European nations in terms of a percentage of the EU average. The blue line represents the national average, the red dots are the regions of that nation and the blue circle is the capital city – which in most cases is the richest region as money naturally flows towards power. Interesting studies have been written on the reasons behind the exceptions like Germany and Italy.

The sharp-eyed will note that the UK has been blanked from the above chart so what happens when it is added back in?

Britain is not Great. Britain is Weird.

Britain is by far the most regionally unequal countries in Europe. This single fact is the cause of a great deal of the economic strife in the country and should be considered the single greatest priority for change of any government attempting to fix the economy.

But what would Scotland look like on a chart like this? We’ve been told that we would be the “Greece of the North”, an impoverished nation bereft of our financial lifeline from our UK benefactors. But if we look to data like this and pull Scotland out from it:

Maybe we’re more like the “Belgium of the West”. And, again, this is before we take the opportunity of independence to build our country to its potential.

So, can we afford to be independent?

Maybe the better question is, can we afford not to be?

This work is part of Common Weal’s White Paper Project which aims to reinvigorate and remake the case for independence. We are entirely reliant on the generosity of small donors, both one-off and regular, to be able to do this work. If you would like to contribute, please visit our website at: allofusfirst.org/donate/

Pingback: SIC Build Conference Slides | The Common Green

Your key on slide re Unequal Union is wrong, trying to show someone and got a bit confused, Scotland is blue not red, surely.

Apart from that, I really enjoyed your input on Saturday.

LikeLike

Oops. Not sure how that happened or how I missed it but cheers, that’s it fixed.

LikeLike

Where does the Bank of England come in? I see you mentionned foreign reserves, what about our share of nationalised industries like coal, forestry and the Bank of England?

LikeLike

You’ll be interested in my paper on splitting assets and debts.

https://thecommongreen.scot/2016/09/02/claiming-scotlands-assets/

There’s a principle when countries split whereby, generally, resource assets and other non-movable assets like government buildings are split on a geographic basis. It’s only moveable assets that get split on a population or other basis (if they do).

LikeLike

Pingback: 2017 at The Common Green | The Common Green

Pingback: We Need To Talk About: The Deficit | The Common Green