The Sunday Times has published a hack-job of a piece attacking the Scottish Government’s proposed plans to change the rates and bands of income tax in Scotland.

They’ve clearly tried to use the Scottish Conservative’s current favourite economic soundbite, the Laffer Curve, to try to build their case that we should be cutting taxes and have sought out a quote from the originator of the idea to try to back it up.

The problem is, I’m not entirely sure that the paper really understands what this idea actually says about tax.

So, you’ve been elected as a politician and appointed as Finance Minister. You’ve decided what things you want to tax and now you’re asking yourself what rate to set the tax at so that you can get as much revenue as possible.

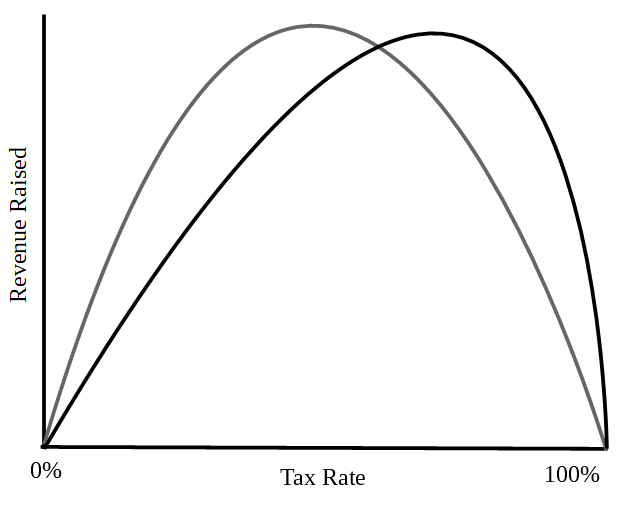

The Laffer Curve was named for American economist Arthur Laffer but its concepts have been noted for centuries. It states that if you set your rate of a certain tax – say, income tax – at 0%, then you will gain zero revenues because you’re not taxing anything.

It also says that if you set your tax rate at 100% then you will also receive zero revenues because if you try to take absolutely everything that someone earns then they will leave the country, they will rebel and throw you out of power or they will find some way to evade or avoid the tax.

So if rates of revenue are zero at each end and we know that setting the tax to some rate between 0% and 100% results in some revenue then there must be, somewhere, an optimum rate of tax which maximises your revenue.

The thing about this principle is that – barring the two end points – economists and political parties can never seem to agree on the shape of the curve or where the peak of it lies.

Often when the debate about tax rates appears in political discussions this topic will come up with some parties – often those on the left of the political spectrum – arguing that the tax rate can be increased and it’ll bring in more money whereas other parties – often those on the political right – will argue that a lower tax rate will reduce evasion and encourage more higher rate tax payers to come to the country and so THAT will increase revenue.

It is difficult to say who is correct for any given tax change at any given time – precisely because no-one can agree on the shape of the curve.

It may well be a fairly symmetrical affair where rates of evasion grow only gradually after the peak is reached. It may slope up gently as rate rise until it hits some cliff-edge after which almost everyone evades the tax at the same time.

It may be that the tax in question interacts with other taxes. One means of avoiding income tax if you own a company is to pay yourself only a modest income and take the rest as shares and dividends. You’ll pay capital gains tax on those earnings but if the rate of that tax is lower than the rate of income tax then you’ll pay less tax in total. This means that your likelihood of avoiding the income tax may depend on what the capital gains rate is. If they’re both the same or if capital gains tax is higher than income tax, then there would be no point in using this trick (indeed, the reverse trick – taking less income as dividends and more from a direct salary – might become the one used to minimise tax payments).

There are also other costs, beyond just the tax rate. If the “cost” of outright evading a tax is a small fine and a slap on the wrist, then it might be “worth” the risk of doing it and getting caught but if it involves a lengthy jail sentence then perhaps not.

We can also see that simply evading a tax isn’t the only way of interacting with it. Revenue from consumption taxes like VAT depend on the spending habits of consumers. If VAT is set too high, then consumers may buy fewer products or switch to products which are exempt from the tax. If the economy itself is doing poorly then people may not have enough disposable income to spend on consumer goods even at low rates of VAT whereas if the economy is doing particularly well then people may be able to afford to spend even with relatively high rates of VAT. Of course, economies can grow and contract so the “optimum” rate of tax may change with time.

Finally, it may be the case that a government is not seeking to maximise revenue from a given tax. Some taxes are designed not to raise revenue but to reshape society by encouraging or discouraging certain behaviour. A good example of this would be a tobacco or alcohol duty which is designed to limit the amount of these substances that people consume and to raise enough revenue to compensate for the negative health effects and other costs caused by that consumption. Another might be a financial transaction tax which, at low levels, raises revenue from rapid, short term stock and share trading but at higher levels seeks to limit such activity and the instability it can cause in the broader economy.

After all of these considerations, the evidence for increased revenue after a tax change (in either direction) can also be difficult to measure as it can be masked by other changes in the economy such as a general increase in the size of the economy and therefore an increase in revenue from all taxes which would have happened even if they hadn’t been adjusted. As the size and shape of economies change then the rate at which maximum revenue is generated may also change so one can expect the debate to be repeated every few years.

The Laffer Curve is an interesting academic illustration which can be used when discussing tax rates but such discussions should always be underlined by the point that it is never as simple as moving each tax individually. They rarely act completely independently of each other and their effects on the economy may go beyond simply the amount of money raised by the government.

If we’re going to keep using this soundbite in our debates about tax, it is the responsibility of everyone involved to make sure that they know exactly what they are talking about. It’ll help avoid articles like that published by the Sunday Times and hopefully it’ll help avoid scenes like that which happened in the Scottish Parliament when Murdo Fraser tried to push the soundbite past Ivan McKee.

Worth noting that Laffer was one of Reagan’s favourite economists.

LikeLike

And Laffer’s interpretation of the curve was used as justification for Reagan’s big tax cuts for the wealthiest Americans, which is perhaps which sets him apart from historical precedents.

Apologies – interrupted during drafting of last comment.

LikeLike

Laffer is also one of Trump’s economic advisors although he also describes himself as a Democrat so, maybe that says a lot about American politics…

LikeLike

I think he also advised Arrnold Schwarzenegger in California.

On a lighter note,one of the indefatigable letter writers to the Scotsman claimed some time ago to have studied Laffer’s work as an undergraduate (or it may even have been in S5 secondary) at a time when Laffer was himself still an undergraduate (or indeed still in high school) i.e. at the start of the 60’s.

LikeLike

Craig, not sure if the CGT case on taking dividends is entirely in point. There’s now an anti-avoidance provision to avoid phoenixing from one company to another. It’s only the sale of the shares that would bring CGT into play (typically at only 10%) but opportunities now much more limited with the loophole closed; whilst dividends suffer a mixture of 0%/7.5%/32.5%/38/1%.

The important issue now is that the dividend tax does not come to Scotland, for we have powers over earnings only.

LikeLike

I have offered a very highly simplified example here (so as to illustrate an already simplified model of tax). Of course, the real-world examples are going to be much more complex and regulations play as big a role (or a greater role) in preventing tax avoidance as does balancing the rates and definitions.

LikeLike

Timely and important article Craig! May I offer this on the basis that one of the projects I hope to start next year follows these thoughts:

Extract from Scottish Fiscal Commission (SFC) Summary:” …Taxpayers may also change their behaviour in response to changes in tax policy. These may take various forms such as tax avoidance, tax evasion, migration or a change in labour supply. Responses may be particularly large at the top of the income distribution, whereas we would not typically expect much of a behavioural response amongst lower income taxpayers…”

So absorbing that information, am I allowed to suggest the Laffer curve provides a chart – a what, namely tax, and may also track the variables given – a series of hows – avoidance, migration etc.

What is missing? What is missing imho is the why, or more precisely a series of whys.

Why on earth would anyone want to help the disabled as they face cuts to their benefits? Why on earth would anyone wish to help a mother, who having taken her ill child to the doctor, misses her time slot at the Job Centre, and is sanctioned? Why on earth would anyone care about a 5 or 6 week delay in payments under Universal Credit? Or homelessness etc etc.

Laffer poses a question, but is its answer unavoidably correct? Is it missing the why?

What if – we could show in Scotland a way of answering those whys?

What if we could prove the SFC wrong in their prognosis and that they are mistaken in their judgement that there is unlikely to be much of a behavioural response amongst lower income taxpayers.

Perhaps, just perhaps, when we seek an answer not to what, nor to how, as in Laffer, and as in the thoughts of the SFC, we may find answers as to why behaviour changes at the lowest levels – contrary to what too many may believe.

LikeLike

Seems like a interesting topic for a computer simulation. Cellular automata or agent-based. Start with only one tax and simple rules, then build it up with more taxes and more complex rules/interactions. Difficult to verify incrementally, though. Perhaps worth trying if a collaboration could be created with the right mix of skills and knowledge.

LikeLike

Intriguing idea although I suspect that your model will become complex enough to melt a super-computer rather more quickly than one might expect. Also, I can’t code worth a sausage so I’m going to have to offer the challenge up for someone else who fancies giving it a go.

LikeLike

Pingback: 2017 at The Common Green | The Common Green

Pingback: Excluding Growth | The Common Green