“The Master said, “If your conduct is determined solely by considerations of profit you will arouse great resentment.” – Confucius

This blog post previously appeared in The National as part of Common Weal’s In Common newsletter.

If you’d like to support my work for Common Weal or support me and this blog directly, see my donation policy page here.

Common Weal has been campaigning for the best part of a decade on overhauling and improving the Scottish housing sector. While we haven’t been named in the announcements, the SNP’s new proposal to launch a National Housing Agency should they return to Government after the elections is a policy taken straight out of our strategic roadmap which called for what we termed a Scottish National Housing Company.

It is far too easy for Governments to talk big about housing but to do little. Even in previous election campaigns, it has been considered sufficient for a political party to just look at the raw number of houses being built in Scotland and to either say that they would build X thousand homes (where X is a larger number than their rival party is promising to build, or that the previous government actually built) without paying much attention to other vital factors such as where the houses are built, what standards they are built to, how much they’ll cost, what kind of tenure will be offered to residents or who will profit from the construction of the buildings (particularly if policies come with significant amounts of public money attached). This number goes up and down with the political winds but rarely is it based on anything other than that kind of political party promise. It’s almost certainly never based on whether or not that number of houses is ‘enough’ to satisfy immediate and long term demand.

In these respects, the Government has been taking some welcome steps particularly with policies around rent controls and energy efficiency standards (though we still have significant disagreements around how far those proposals should go – the current rent control plan all-but guarantees above inflation rent increases and the energy efficiency standards appear to be being significantly watered down from the “PassivHaus equivalent for all new homes” originally promised).

But a more strategic approach to housing is still needed beyond piecemeal interventions and broad frameworks so in this respect, that the Government has adopted our Housing Agency is something to be celebrated.

The devil is in the details however and Common Weal is now gearing up to develop our proposals and to try to ensure that the Government adopts them in full.

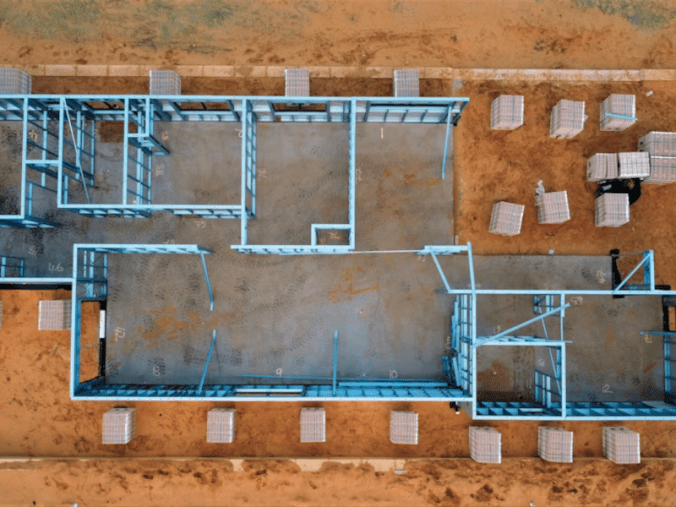

In our original plan, the Housing Agency would be a direct construction body – public owned and employing the people who actually build our houses.

Direct construction bypasses the biggest limitation of every housing policy that has come before. Private housing developers aren’t in the business of building ‘enough’ houses. A basic rule of economics is that price is determined by supply vs demand. Scarcity results in higher prices. This means that developers can charge higher prices by not building homes as quickly as they could or by “banking” land they own to prevent another developer from buying it and building (see my article in In Common last November which breaks down why this and other factors increases the price of an average UK home by around £67,000).

We also can’t keep building houses purely to chase the highest possible price when it comes to tenures. We’ve heard a lot about “affordable homes” in recent years despite no real definition of what that actually means beyond developers being forced to sell a few homes in each block of houses a little bit cheaper than they otherwise would (even when “a little bit cheaper” is still very much unaffordable for many).

A strategic plan led by a National Housing Agency would not be concerned about quick profits and so could build houses with a longer term view. Housing for social rent especially should be built to a standard that minimises ongoing costs like heating and maintenance thus makes living in the houses cheaper for social tenants. (See my 2020 policy paper Good Houses for All for more details on how that would work).

This would benefit Local Authorities in the long term as once the construction costs of the houses are paid off in 25 or even 50 years time, the ongoing rents will still provide a safe and steady income for decades to come. By contrast, the cheap and flimsy houses being built today are being put up by developers who don’t particularly care if the house outlives its mortgage – if it doesn’t, they’ll happily sell you another one.

This is the important point about the role of a National Housing Agency. It cannot be a mechanism for laundering public money into private developers. It absolutely must be a force that outcompetes or plays a different game from the private developers. It must disrupt the market to the point that people would actively seek out a high quality, efficient and cheap to live in Agency house rather than a private developer “Diddy Box”, especially one being offered at exorbitant private rents because the only people able to actually buy them are private equity funded landlords.

Houses should not be an inflatable capital asset designed to enrich the already wealthy and to suck wealth out of the pockets of everyone else. Houses should, first and foremost, be a home. This is the measure of the ambition that the National Housing Agency should be aiming to achieve. Common Weal is very happy to see this policy enter the politician discussion space. We stand ready to help whichever Government comes out of the elections this year to build the Agency we need so that it can build the homes that all of us deserve.