“What are the odds that people will make smart decisions about money if they don’t need to make smart decisions—if they can get rich making dumb decisions?” – The Big Short

This blog post previously appeared in Common Weal’s weekly newsletter. Sign up for the newsletter here.

If you’d like to support my work for Common Weal or support me and this blog directly, see my donation policy page here.

Image Credit: Dominic Alves

Image Credit: Dominic Alves

Rachel Reeves has signalled that she is “open minded” about the banks lobbying her to repeal regulations that came in after the 2008 Financial Crash. If she does, she will be accepting responsibility for the next one the banks inevitably cause.

One of the most important films dealing with the financial sector since the 2008 Financial Crash was 2015’s The Big Short. Comedic, irreverent and outright scathing of those involved, yet it remains one of the most incisive explanations of the 2008 Financial Crash and it managed to make the intentionally obscure world of financial alchemy accessible to the lay person. I’d go as far to say that it did for the idea of ‘sustainable investment banking’ as the films Threads and The Day After did for the idea of a “survivable nuclear war”.

If you haven’t seen it, please do so and pay particular attention to the scene explaining the concept of “synthetic CDOs” – where investors could effectively gamble on the possibility of you defaulting on your mortgage, and other investors could gamble on whether or not those investors will win their bet, and more investors could gamble on the outcome of those bets…all without knowing anything at all about your finances and the state of your mortgage.

One of the things that made these ‘financial instruments’ so destructive was that the ‘investment’ side of the banking sector – the bit that involves people effectively gambling amongst themselves with money that maybe was theirs and maybe wasn’t – was entirely leveraged on the ‘retail’ side of the banking sector – that’s the bit where you put money in your savings account and ask the bank for a mortgage to buy a house – but was completely divorced from it to the point that one side didn’t understand what the other side was doing.

When the housing boom of the early 2000s came to an end in late 2007 and people started defaulting on mortgages, this would have normally been tragic for those losing their homes and a sign of a substantial economic recession but would have ultimately resulted in a bounce back. But all of those ‘investment firms’ sitting on top of the sector were gambling with money that they ‘knew’ was ‘safe’ (because ‘safe as houses’) despite the houses not being nearly as safe as people assumed.

Not just assumed. The way the CDOs were structured made it functionally impossible for anyone to actually assess the risk of their failure. Because it was impossible to work how and if they might fail, the credit agencies declared them to be safe (yes, really) which encouraged banks to pile money into them.

It got so bad that the investment sector was gambling with something like $20 for every $1 actually involved in the mortgages. The investment gambling sector was many times larger than the value of thing they were gambling on. The liabilities on the banks ‘if’ their sure bet failed reached the point of being larger than the GDP of the countries they were based in.

It would only take a small increase in the percentage of mortgage defaults to utterly bankrupt the banks. An increase that might be caused by investment bankers encouraging retails bankers to take on ever riskier mortgages (with ever higher profit margins), paying exorbitant bonuses to bankers who could sell larger and larger mortgages to people who couldn’t afford to pay them.

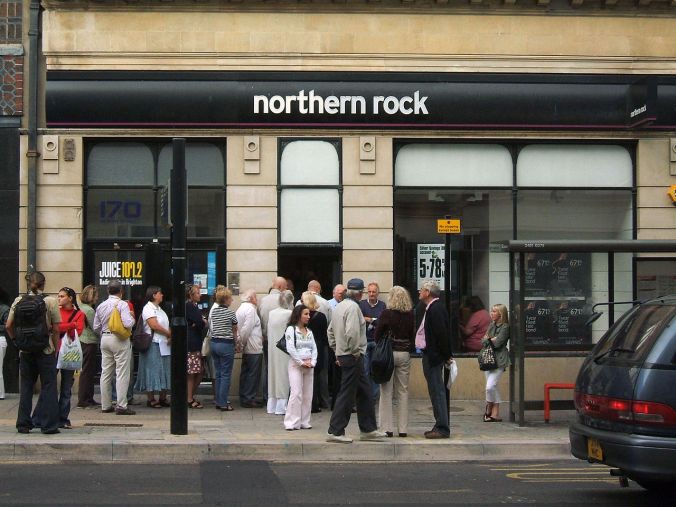

Which is what happened. And the backlash threatened to pull down other sectors of the economy because the bankers weren’t just gambling on mortgages but on everything just about up to and including whether or not the sky was blue and the fact that the investment wings were entwined with their retails wings meant that if their investment bank failed, the ATMs on the high streets could be shut down too (runs on banks like Northern Rock showed the visceral reality of people faced with losing their savings because of someone else’s mistakes).