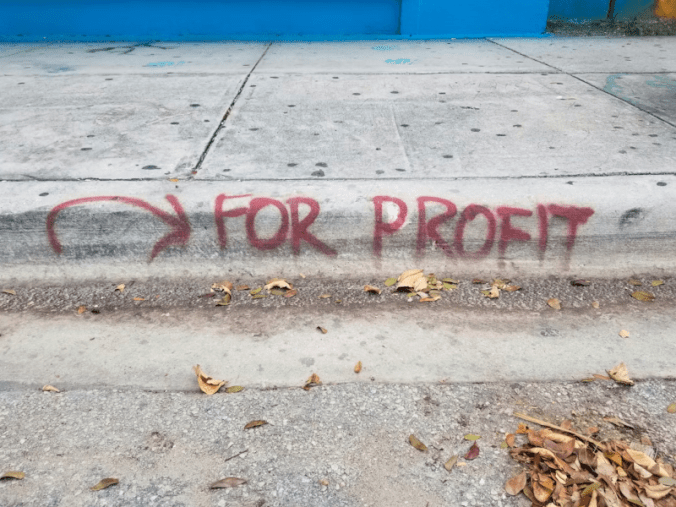

“It’s called socialism. Or, for those who freak out at that word, like Americans or international capitalist success stories reacting allergically to that word, call it public utility districts. They are almost the same thing. Public ownership of the necessities, so that these are provided as human rights and as public goods, in a not-for-profit way. The necessities are food, water, shelter, clothing, electricity, health care, and education. All these are human rights, all are public goods, all are never to be subjected to appropriation, exploitation, and profit. It’s as simple as that.” – Kim Stanley Robinson

This blog post previously appeared in The National, for which I received a commission.

If you’d like to support my work for Common Weal or support me and this blog directly, see my donation policy page here.

Scotland has an extremely poor track record of benefiting from our own energy resources. The decline of the First Age of energy wealth – based on coal – can still be seen in the scars of deprivation it left behind especially in the Central Belt towns and villages around where I live and where mining was most intensive.

In the Second Age, our oil wealth was – as Gavin McCrone warned – downplayed and then squandered under successive UK Governments while leaving Scotland vulnerable to oil shocks and we’re now seeing how we’re being held liable for the costs (economic and social) of drawing down the sector as it absolutely must be drawn down as the world wrestles with the challenges of the climate emergency caused largely by that oil even as the rich owners of the assets reap the profits and continue to lobby to delay or prevent change.

The problem is that unlike almost every other country that found itself with large reserves of energy wealth, we collectively decided that Scotland shouldn’t own any of it.

Rather than building up a robust public-owned oil sector, the UK Government flogged off the rights to exploit the resources to the lowest bidder, even offering generous subsidies rather than taxing their profits. The downstream infrastructure was privatised too not just sucked vast amounts of wealth into the pockets of billionaires like Jim Radcliffe but also granting them vast political power and the ability to make hypocritical statements about immigration while living the high life in their own offshore tax haven.

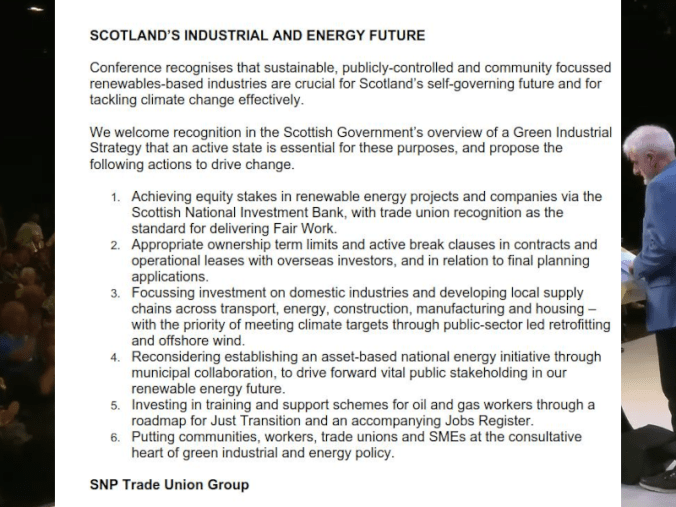

The Third Age of Scottish energy is our Green Transition – built initially around our vast onshore and offshore wind resources but now increasingly diversifying into other areas like solar and battery storage.

We see here that Scotland is in the process of losing out once again when it comes to energy resources that, if anything, vastly outstrip anything the oil sector could have ever promised because, unlike oil, the sun and the wind will continue to deliver that energy long after the last barrel of oil is extracted from the ground.

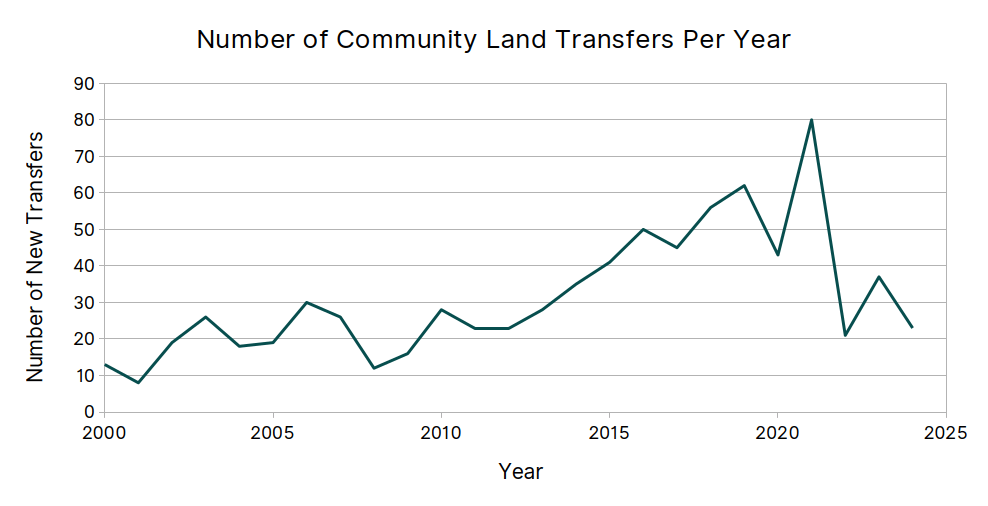

It promised to finally bring some ongoing benefit to communities that would be hosting the generators but even that failed. Neither Scotland nor the UK showed interest in developing public ownership of the assets and the “community benefit” funds were set at the lowest possible level of £5,000 per MW of capacity for wind (not uprated for inflation) and zero for other forms of renewables. It is estimated that a community owned wind turbine generates around 34 times as much revenue for the local community as does a privately owned one that pays its £5,000/MW community benefit. There is some evidence emerging that even this paltry sum is not being met in many cases with The Ferret reporting a shortfall of about £50 million across Scotland’s community benefit funds.

Offshore is arguable worse with the debacle of the ScotWind auction selling off the options to develop one of the largest offshore wind projects in the world in an auction that, for reasons still not adequately explained, set a maximum price cap on bids and potentially cost Scotland anywhere between billions and tens of billions of pounds in upfront capital.

Most crucially of all, we don’t even make the renewable generators and batteries that we don’t own. Decades of climate-denying politicians telling people that we shouldn’t bother trying to avert climate change because China wasn’t doing anything conveniently ignored that China was, in fact, rapidly building up its industrial base and was starting to sell the generators to the world.

So Scotland now imports the materials to build wind turbines that are owned by multinational companies and foreign public energy companies that export their profits elsewhere and pay communities sometimes less than the bare minimum. We don’t even get cheaper energy for it because the UK’s grid and pricing structures are still based on assumptions laid down in the Coal Age.

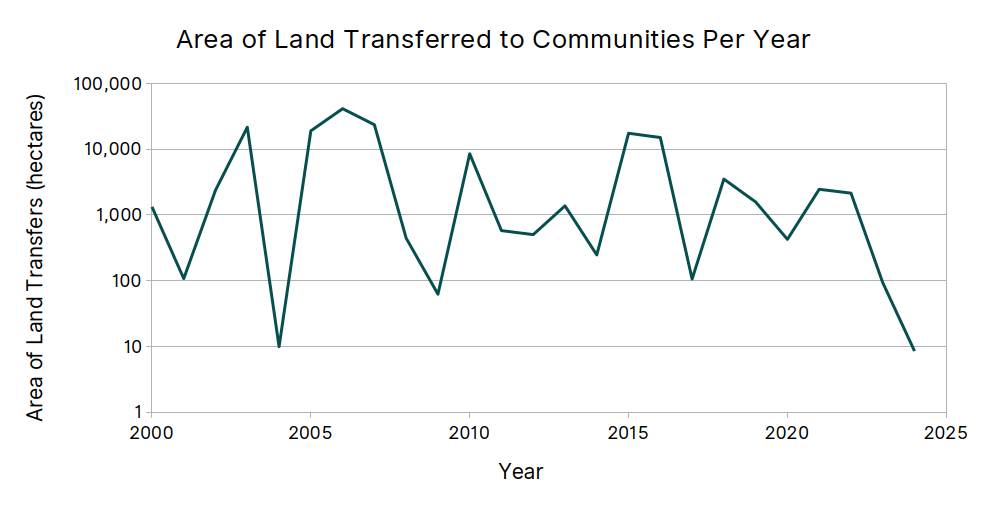

So what of the Fourth Age of Scottish energy? The thing about the current generation of privately owned energy assets is that they will eventually need to be replaced, and fairly soon – perhaps in 25 years time. This gives us an opportunity to start planning now.

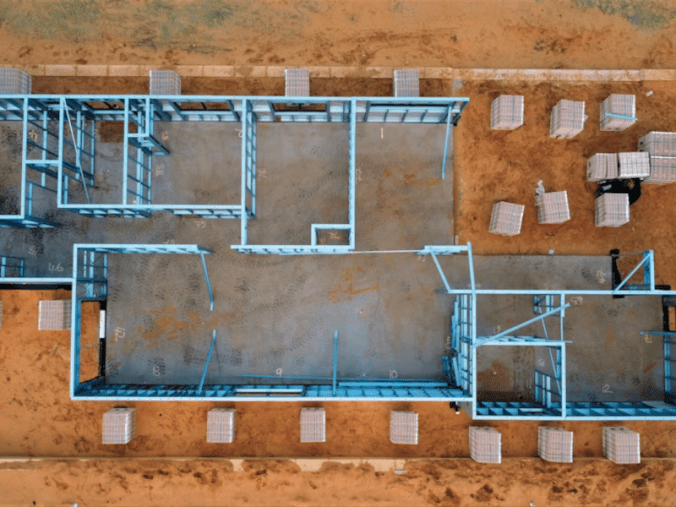

Scotland needs to start building up its domestic wind and solar manufacturing base. We need to use our excellent universities to develop the materials to ensure that those generators are built to Circular Economy standards (current generation fibreglass wind turbine blades are disposable and are sent to landfill after use). We also need to start aggressively bringing assets into Scottish public ownership. Every time a renewable energy lease is up for renewal, it should be transferred to a Scottish public energy company (nationally or locally owned). This can also happen when a site is up for “repowering” – when old, smaller turbines are replaced with larger, more powerful ones but which exceed the previous lease’s maximum capacity terms.

New renewable sites should have their leases signed aggressively in favour of public ownership too. Rather than 60 or 99 year leases that cover the lifespan of multiple generations of turbines, they should be set to as low as 10 years. Enough time for the private developer to recoup their investment but also enough time for the Scottish public sector to take over the site and also make a profit without merely being saddled with the liability of decommissioning as we’re doing with the oil sector.

If any of this is not possible within devolution (some of it certainly is) and the UK is not willing to allow it, then while we are doing what we can, the case must be made for independence so that we can finish the job.

All of this will take time to set up which is why we need to start preparing the ground now. I don’t want to be here in 25 years talking being asked to comment on why we’re importing the next generation of technology and exporting the profits again. If we want to sit under a tree in 2050, maybe the best time to plant it is today.