“Unless Scotland has the boldness and the courage of its convictions to use the abilities that the Scottish Parliament is going to have in the next session to have a fairer, more progressive approach to taxation…many more communities are going to find that the public services they rely on will continue to be under threat.” – Patrick Harvie

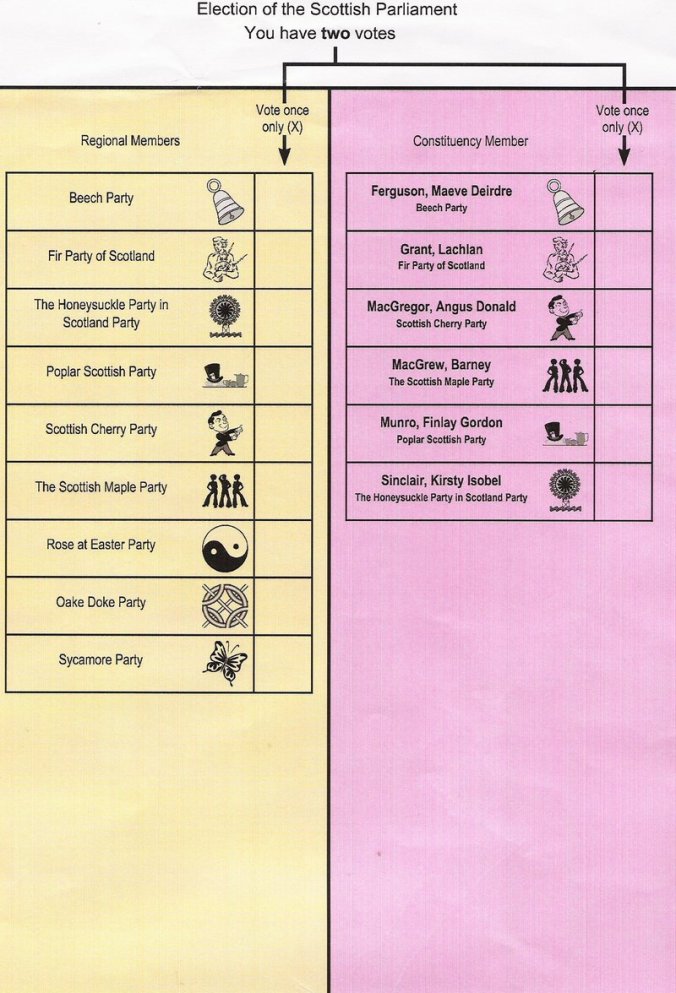

Yesterday, the Scottish Greens published our proposals for reform of both the national income tax and a replacement for the local council tax. The proposals themselves can be read by clicking on the image below but I’ll spend a bit of time here explaining how they work and what might have been missed in some of the media coverage about them.

First though we need to remember just what the purpose of tax is for. It’s so easy to get caught up in the arguments over how much more or less a particular tax or tax change would raise without considering the deeper impacts of what a particular tax is supposed to do.

The Principles of Taxation

Why do we tax people in the first place? It’s a substantial chunk out of your paycheck every month and there’s not one of us who has, at some point, wondered what they could have done with that money instead.

The reasons for taxation are broadly covered by three principles:

Revenue Generation:- There are many services, such as roads, emergency services, healthcare, education etc, which we, as a society, have decided are best funded collectively. We may argue over just how much is paid for in this way and how much is funded ad hoc or privately but there are vanishingly few full blown anarcho-libertarians, especially in Scotland, who believe that absolutely everything should be in private hands and that Government shouldn’t exist at any level. For everything else, taxes are collected to fund the State and its operations.

Redistribution:- Societies are rarely entirely equal at every level. Some people end up earning or accumulating more than others, some people end up not earning enough money to meet their basic needs. Some regions end up with a greater concentration of wealth than others. Some, due to size or geographical constraints (such as the Highlands and Islands) simply require more funds to deliver the same level of services than others. It is well known that more equal societies experience greater levels of wellbeing and lower levels of ill health and other negative effects. Most societies, therefore, employ tax, alongside policies such as social security and welfare, in a progressive manner such that the richer pay more according to their abilities and the poorer gain more according to their needs.

Reshaping:- This is the carrot-and-stick approach of taxation. Governments often develop policies designed to encourage their citizens towards certain activities or discourage them from others. One prominent example at the national level would be the levies on tobacco and alcohol which are, at least partly, there to try to encourage us to smoke and drink less (obviously, taxes can fall into multiple categories and the Revenue Generation aspects of these taxes cannot be discounted, especially when used improperly).

In addition to these principles on the purpose of a tax, we must consider how it is structured so that it works in an effective manner. In 2013, local council body COSLA published a report into the effectiveness of current local taxes and in it laid out six principles outlined below.

Essentially, these principles boil down to taxes being fair, easy to manage and employing a sense of subsidiarity whereby local powers should, wherever possible, be used to effect local solutions. Whenever discussing a potential tax, local or national, all of these principles must be upheld or accounted for.

Income Tax

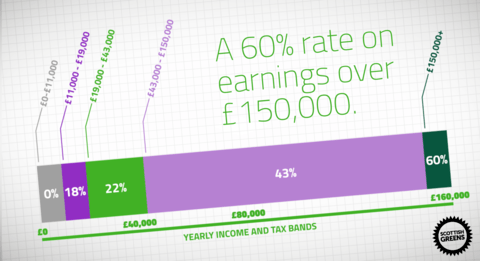

The Green proposal for the use of the income tax powers due to come with the implementation of the Scotland Act 2015 includes not just a tweaking of the rates nor the use of clumsy rebates as Labour (briefly) seem to have considered but the full use of what powers we shall have to create new bands appropriate to Scottish income distribution.

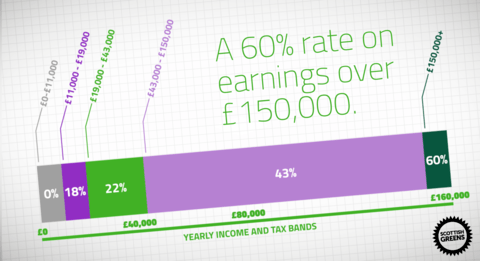

The headlining feature of these proposals, as one may have suspected, was the inclusion of a 60% rate on earnings over £150,000.

This certainly did grab the headlines coming so soon after the SNP announced that they would not be raising the top rate past it’s current 45%. Their decision was based on this document which suggests that the “tax induced elasticity” (TIE) of the richest 1% in Scotland may be substantially higher than in the UK as a whole. Simply put, they fear that Scottish millionaires may flee elsewhere if we tax them at a higher rate than their southron counterparts. Their claim is that in the worst case scenario, enough high earners would leave that the actual revenue collected could be up to £30 million less than would be if tax rate remained as it is (one has to remember that if a top rate tax payer leaves, you also lose what they’ve paid in lower bands too).

Now, I have a couple of reasons to doubt this will impact as badly as they fear. In particular, having had a read through the book on which the UK TIE figures are based and having back-calculated their suggested maximum top-rate income tax for those UK figures, the implication appears that if the high end TIE rate the SNP suggests (0.75 compared to 0.46 for the UK) were to come to pass the maximum allowable income tax rate would be something on the order of just 30%. I would suggest therefore that the conviction attached to that worst case scenario is somewhat low as not even the Scottish Tories have went into this election on a platform of cutting the top rate of income tax.

My other reason for skepticism over this fear of tax flight in relation to internal tax boundaries is the case actually seen in the United States (In particular, as found by this paper by Young et al in their study of tax migration and border effects) where each state has far more control over many taxes than Scotland has and consequently sees quite sharp tax boundaries between states. Now this is not to say that that tax induced migration does not occur but in the words of the paper linked to above it seems to occur “only at the margins of statistical and socio-economic significance”. This appears to be true even at easily commutable borders so don’t be readily expecting a cluster of Scottish millionaires moving to Carlisle or Newcastle.

[Edit: Alternate link to the Young paper here.]

The reason for this is quite profound. As it turns out we can broadly place the richest echelons of society into to one of two groups. The “transitory millionaires” who really are just seeking somewhere to park as much of their wealth as possible without contributing much to society in general and the “embedded elites” who more closely fit that classic-to-the-point-of-cliché term of “job-creator”. These folk are the ones who have built a business in their locale and, as it turns out, it is not a simple case to uproot it and move it wholesale elsewhere (especially when higher property prices may make the operation of that business significantly more expensive). Perhaps, we in politics have been too quick to conflate these two distinct attitudes among the most well off in society. Perhaps we should instead be asking which of the two groups we would prefer to have influence our policy decisions?

On the Greens’ part, we are not making any prediction of revenue based on our 60% rate. We’re operating on the basis that our changes to the top rate of income tax will not attract any additional revenue (although the changes overall could bring in some £331 million per year) and this managed to attract some attention during the recent STV Leader’s Debate with the Tories asking what the point was if revenue didn’t change and asking how that would improve the economy. Well, we’ve seen the answer to that in the principles section above. The Green tax plan would significantly reduce inequality within Scotland. From a social standpoint, this should significantly improve general wellbeing within Scottish society and from an economic standpoint there will be benefits due to what’s known as the Marginal Propensity to Consume. Essentially, if you increase a multi-billionaire’s income by £100 then it means next to nothing to them or their lifestyle but if you increase the income or decrease the tax burden of a minimum wage worker by £100 then it will give them the ability to pay down debts or spend more on goods and services on which they would not otherwise have been able to do so. By this means, a revenue neutral tax change which decreases inequality most certainly can have a positive economic benefit. It reflects poorly on Ruth Davidson that during that debate she either didn’t know or didn’t want others to understand that fairly fundamental point.

Property Tax

Incidentally, the Young paper linked to in the previous section points out that a far more significant cause of high-earner migration than income tax is a draw towards expensive housing which is a famously immobile asset and which leads us neatly on to the second half of the Greens’ proposals.

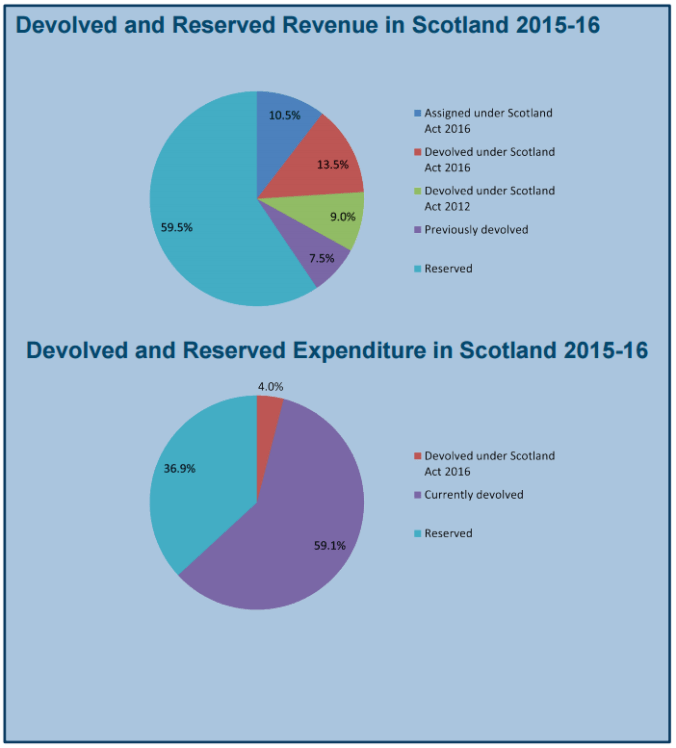

Given how limited the set of devolved national taxes actually are and given how long overdue we have been for doing something, anything, about the Council Tax, it’s perhaps no surprise that a large proportion of the campaigning has been dedicated to those taxes over which Holyrood does have near unfettered control.

Faced with the increasingly loud rhetoric over the need for change from many parties and the cross-party consensus on the need for radical change laid down by the Commission on Local Tax Reform’s final report it’s therefore been a deep disappointment that it has been left to the Greens to be the only party to lay down a system of local residential property tax which is meaningfully different from the Council Tax. The Lib Dems have dropped their long standing aspiration towards a local income tax. RISE have stuck to the plan for an income based service tax inherited from the SSP but have appear to have opted to set rates nationally thus remove the advantages of local control. The SNP have decided to keep the present system, including the quarter century old, out of date valuations, but will increase the rate multiplier, nationally, on the top couple of bands. Labour have come up with a system of a per household flat rate poll tax with the addition of value based percentile tax (In my previous article I mischaracterised this as a banded tax due to a misunderstanding of their press statements on the topic. I was in error.) which, on the face of it, is an interesting change but their actual calculations will leave us again with a tax which is deeply regressive with respect to house value.

The Greens, however, have opted to levy a local property tax based entirely as a percentage of the property’s value. This Residential Property Tax would be nominally set to 1% of the property’s value but it will be entirely within the local council’s power to set that rate at whichever value they wish and will be coupled with a scheme of reliefs for low earners similar to the system currently in place.

Of course, such a large step change in the tax system requires careful management and people will need time to adjust their financial affairs to reflect the change so we also propose phasing in the new RPT over the course of the next five year Parliament by stepping over to the new system in 20% increments until Council Tax is fully abolished.

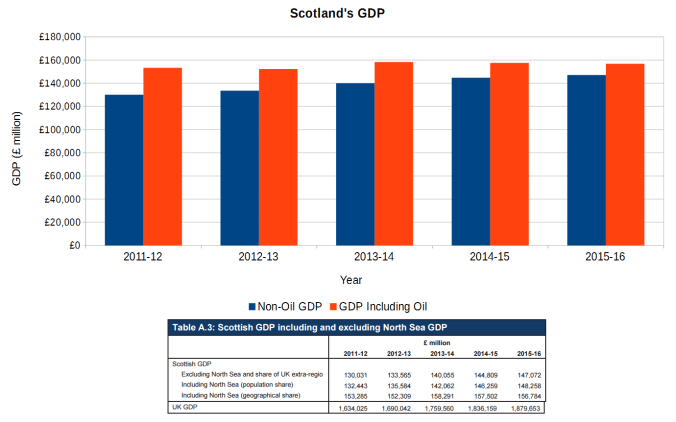

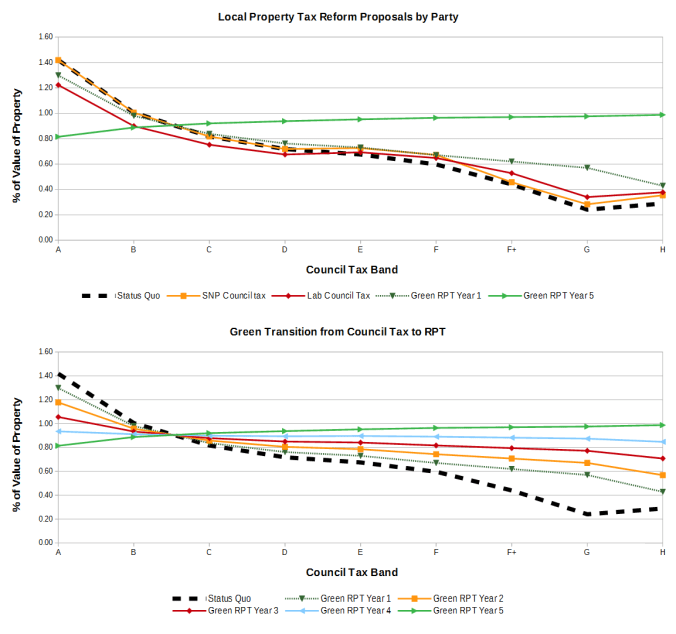

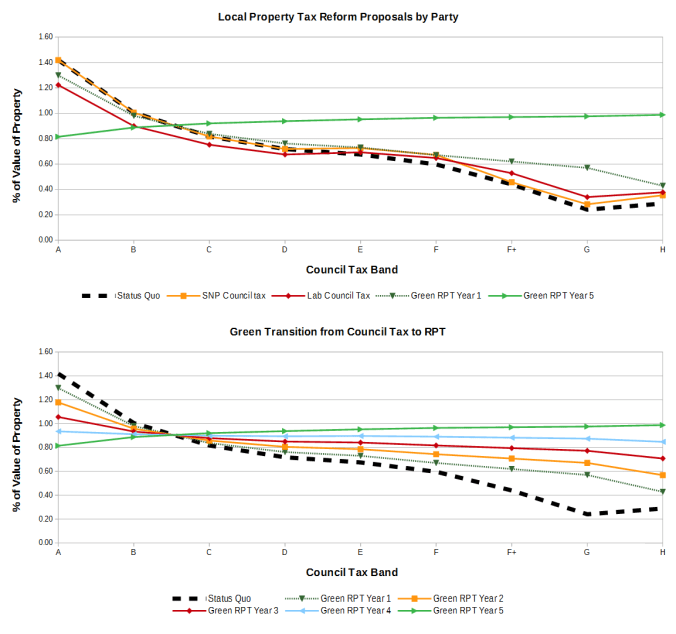

The graph below shows this transition as well as a comparison of the tax regimes proposed by the SNP and Labour as a percentage of a house’s value (RISE’s SST, being income rather than property based, isn’t directly comparable in this way).

The contrast is quite profound. Incidentally, the large change in nominally band “C” and above properties may look alarming but one must remember that the lack of revaluations since 1992 has led to many houses, some 57% of the total stock, sit now in the wrong council tax band. The house I’m currently in is a fairly graphic example of this being a band “D” house with a present market valuation of approximately £100,000. Converting from the present Council Tax to a 1% RPT would actually cut the bill here by some 10%.

Also of specific note within these plans is a system of redistribution across councils. Essentially, there are some council areas containing a lot of very expensive houses (Edinburgh, say) and some where property prices are comparatively cheap. It couldn’t be fair that one of the higher priced areas takes the decision that they could cut property taxes to a bare minimum and still fund local services, as happens in places like Westminster, whereas lower priced areas must pull those tax levers harder. Therefore, the block grant given to councils will be calculated on the assumption that they will charge the 1% RPT which will remove much of the temptation from those councils with higher property values from perpetuating the cycle of inequality. They still would have the power to reduce those rates, but they’d have to be accountable to their voters for doing so.

But what of land? Isn’t that a core tenant of Green policy? Well, herein lies an aspect of property tax which has been almost entirely missed by the media and yet lays the path towards possibly the greatest change within them. The RPT includes a slider which will allow a council to weight the RPT between taxing property and taxing land. If a council decided to, say, weight 100% towards property and 0% on land then the system would look most like the present council tax (albeit, as said, greatly more progressive) whereas if another council weighted 0% on property and 100% on land then the system would be functionally equivalent to a Land Value Tax and those who owned not just a large house but also a large estate would have to account for those holdings. In practice, many councils will seek some compromise between the two and the Green proposal lays out an example as currently used in Denmark where a typical weighting is something like 70% on property and 30% on land. Once again, localism is the key here. Council regions which are largely urban will likely wish to weight towards property whereas more rural areas, particularly those with patterns of unequal land ownership, may wish to weight towards land. Simply setting a national rate is unlikely to be sufficient or effective in every region of the country.

Conclusion

I hope this then lays out our proposals for income and property taxation. I know. It’s a complicated issue which doesn’t soundbite very easily but we’re entering an interesting phase of Scottish politics whereby our Parliament will be getting more power than ever before and the need to use those powers effectively will become more important than ever before. Scotland Can be bolder if we want it to be.

My thanks to Andy Wightman for technical advice provided for this post. His blog Land Matters can be read here.