“Diplomacy is the art of letting someone else have your way.” – Sir David Frost

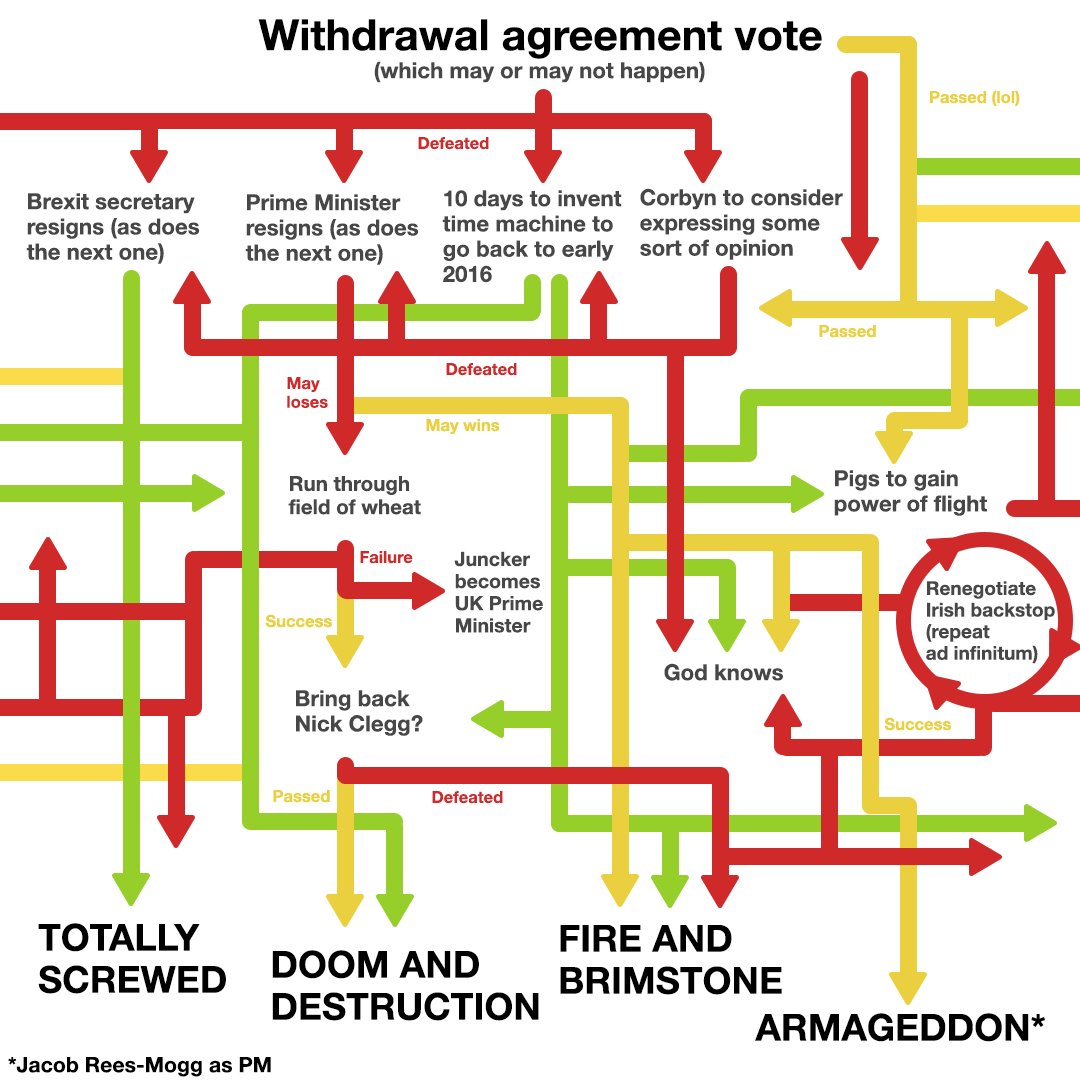

I was preparing this week to talk about the “Meaningful Vote” in the House of Commons which would have ratified or rejected Theresa May’s woefully inadequate Brexit deal.

But things have progressed somewhat since I started planning that post. In a direction not necessarily to the advantage of the UK government. Theresa May, Strong and Stable, took her deal from the table. She started into the face of the humiliation of losing a vote possibly by a triple digit majority and ran away to try to renegotiate with the EU – who have already said that renegotiation is not possible. If it turns out that they were not entirely solid on that principle, then they’ll surely exact a high price for any changes.

I don’t think it’ll matter. Any concessions will be too small to make any difference (any larger and they’d breach the UK’s irreconcilable red lines). The main one that May seems to be around making the backstop “temporary”. But this fundamentally (and perhaps deliberately) misunderstands the function of a backstop. The backstop is the outline of what happens if the plan fails. They are the bottom of the cliff. If the UK, having stepped off the cliff, wants to avoid the bottom, it needs to build a working aircraft. If it wasn’t an oxymoron, a “temporary” backstop would risk the UK hitting the bottom and not knowing how far down that would be.

That whistling sound is the cliff rushing past.

Scotland needs to prepare for all eventualities. A lot could happen to the UK very quickly. The question of independence may be ratcheting up again and the public mood seems to feel it. A recent poll found that 59% of people in Scotland considered independence to be better than a hard Brexit and 53% of people considered independence to be better than May’s Deal. This is fertile ground for a majority of support when the time comes.

It’s fair to say that we’ve never been more prepared for the challenges of starting a new country. The strengths of the 2014 case have been built upon. Its weaknesses largely addressed. The shifting ground adapted to far, far more adeptly than our counter-parts on the Unionist side have adapted their case.

But there are still challenges ahead that the pro-independence campaign needs to address (and that the Unionist side never will – they only need to throw their hands up and claim that everything is too difficult so why bother trying). One in particular is becoming more apparent as the disaster of the Brexit negotiations reaches its crescendo. We need to work out how Scotland actually withdraws from the UK.

Not in the sense of declaring independence. That’s relatively straightforward if both sides are agree that it’s going to happen.

(If one country doesn’t, well…)

I’m not even talking about the part of the negotiations covering separation of debts and assets. That process is now reasonably well established and options are pretty clear. It’s not even really about building up the institutions that we currently don’t have but will need upon independence. We’re talking about separating something both more insubstantial and more foundational to a new country. Our laws. For what is a country, really, but a mark on a map where a particular set of laws are applied?

The process of Brexit has been one of the UK “Taking Back Control” of its laws by translating the laws currently shared across the EU28 into UK law where, if desired, the UK would later be able to modify them as it sees fit without having to jointly agree with the other EU countries as is the case at present.

(As an aside, Laurie Macfaralane has an excellent article here which deconstructs the inherent problems of the Globalisation Trilemma and the impossibility of having more than two of a choice of global laws, distinct nation states and democratic government)

This process and the speed and extent to which the UK will actually be able to modify formerly-EU laws is at the heart of a lot of the Brexit negotiations with the various factions being torn between those who wish a close relationship with the EU’s laws (perhaps because laws that are hard to change are hard to remove. People who fear a slash-and-burn on worker’s rights are in this camp and not without reason).

But at its heart, the process of the UK repatriating these laws was comparatively straightforward. There is a well established catalogue of EU laws that the UK is subject to and they fall under two broad categories. Those laws which the UK had already translated into UK law (a good example of this being the Mortgage Credit Directive which regulates how mortgages operate across currency borders) and laws which sat at a UK level and needed to be translated over with the passing of the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018.

When Scotland becomes independent, it’s almost certain that we’re going to need a similar Withdrawal Act and now is a good time to consider what it might look like.

One of the issues with Scottish independence when compared to Brexit is that the UK was only embedded within the EU for 40 years compared to Scotland’s 300+ year membership of the UK. It’s also fair to say that Scotland is rather more deeply embedded within the UK than the UK is within the EU. It is conceivable therefore that the act of withdrawing from that union could be legally more complex than withdrawing from the EU. This is certainly an argument that will be deployed against the independence campaign unless we have an answer to it.

Now, I’m not a lawyer – certainly not a constitutional lawyer – so attempting to go into the detail of this is well beyond me but I can see the principles. With regards to Scotland, there are probably three types of laws that we’d have to consider.

- Scots Laws – The existence of a distinct TYPE of legal system in Scotland post-union is pretty anomalous even within the loosest of Federations but nonetheless Scotland managed to keep its distinct legal code as part of the Treaty of Union. Especially post-Devolution, there are laws which affect only Scotland and only exist in Scots Law. The Scotland Withdrawal Bill would not be required for these laws in the same way that the MCD is already a UK law despite Brexit.

- Laws with a Scottish Component – There are laws which affect the whole of the UK but, again due to devolution or for historical reasons pertaining to Scots Law, they are not written as a single act of legislation but are written as separate bills. One, for example, to cover England & Wales and one to cover Scotland. An example of this might be the acts which created separate and distinct versions of the NHS across the UK.

- UK Laws – Finally, there will be those laws which cover the whole of the UK in its entirety and are homogeneously applied throughout. These laws would be the meat of the content of a Scotland Withdrawal Bill as they would need to be either translated across to Scots Law or would have to be rejected as completely unsuitable for Scotland and written from scratch so that they were in place by day one of independence. Financial regulations might be an example of this category (and, of course, whether we translate or re-write may be a political decision in itself). It is possible for countries which separate to maintain some legal ties in this respect and to shadow precedents set before the separation. The Czech Republic and the Republic of Slovakia do this regularly and, in fact, still occasionally reference laws set in their counterpart country POST-dissolution. Depending on “the deal”, the UK may be bound to or voluntarily follow certain EU laws even after Brexit.

With these principles established, the challenge is to go through the books and work out which laws fall into which category and if there needs to be any changes made to adapt them. Lesley Riddoch’s podcast this week identified this problem as an issue to be addressed and mentioned the fact that many might ask if Common Weal would be examining this case. The simple answer is “Yes, but..”

Yes, we’d love to take it on but it’s obviously a huge task, we’re working over-capacity, we’re under-resourced and, as I mentioned, I’m not a constitutional lawyer.

If anyone out there fancies taking on the challenge and writing a paper for us on the subject then please get in touch.

But this really is a job for the Scottish Government. Now is the time to be thinking about these things and I would really hope that they have or are planning to put together a taskforce to take this on. If this is the case, then Common Weal stands by to assist if we’re able.

As of getting to this point in the writing of this post, Theresa May now faces a challenge against her leadership. In about 12 hours, she may no longer be leading the UK (I’ll update this when we know) and the Brexit negotiations could go anywhere. If anything, this heightens the need for Scotland to get started on work on things like the Scotland Withdrawal Bill.

We may need it sooner than we think.

Update: May survived her leadership challenge 200 votes to 117. Clear but closer than she probably would have liked. The Brexit chaos may now resume.

Common Weal is entirely reliant on the generosity of small donors, both one-off and regular, to be able to do the kind of policy work discussed in this article. If you would like to contribute, please visit our website at: allofusfirst.org/donate/

We may well wish to pass a bill regulating the land transport of fissile nuclear materials and giving Holyrood the right to regulate them. We won’t necessarily have to use it but it would signal to rUK that we are serious about Trident leaving our shores and Coulport bunkers and if rUK is tardy in doing so we might just cut it off at the knees.

Before anyone asks the transport by sea is regulated by the law of the sea which is one reason why basing it with the French fleet in Le Havre or in NI would be difficult. That Aldermaston is too far up the Thames for sea transport is not the only reason the warheads go by road, or rail.

We could for include in the law a rule whereby such materials which leave Scotland will not be allowed to return which should concentrate MoD minds.

LikeLike

Pingback: The Final Countdown | The Common Green

Pingback: Sound and Fury, Indicative of Nothing | The Common Green